Adding “Integration” to “Three I’s” and a Maslowian Dilemma: Water Problem in the Middle-East

On October 24, 2014, Jim W. Hall and his colleagues published a briefing on the well-known journal, Science, with the title “Coping with the curse of freshwater variability: Institutions, infrastructure, and information for adaptation”. They argued “adapting to hydrologic variability”, and “building resilience to risk” involves “the three ‘I’s”, namely institutions, infrastructure, and information.

It can be argued that, these levels of adaptation are not only valid for problems associated with hydrologic variability, but also for water management problems at large. While “institutions and governance (including river basin organizations, legal systems, national governments, and nongovernmental organizations) support proactive planning and development of legal and economic instruments to manage and share risks (water allocation and property rights, land zoning, watershed protection, water pricing and trading, insurance, and food trade liberalization”; “investments in infrastructure buffer variability and minimize risks (storage, transfers, groundwater wells, levees, wastewater treatment, and desalination)”. On the other hand, “information collection, analysis, and transfer (monitoring, forecast and warning systems, expert know-how, simulation models, and decision-support systems) are essential for operating institutions and infrastructure.” In other words, all adaptive strategies, or solutions for water management problems operate within a frame defined by these three I’s.

However, as noted by the authors, these are not and should not be thought as isolated nodes. Indeed, they are integrated in multiple ways. Hall et al. concludes “understanding the evolution of risk also means tracking and predicting processes of demographic, economic, social, institutional, and environmental change.” So, we should be aware of dynamics at a great number of planes.

But how can we understand and analyze the interplay of different factors on these three levels? How can we add the integration as the fourth “I”?

Adding integration might be achieved through thinking of all possible solution alternatives under three broad categories, in a holistic fashion and in relation with the “Three I’s” framework. These three broad categories of solutions are: technical solutions, financial/economic solutions, legislative/social solutions.(1) All these solutions need to work in one or more of the three levels, i.e. “Three I’s”.

But this is not straightforward, particularly in the Middle Eastern water context where a Maslowian dilemma, as I would call, prevails. Abraham Maslow, an American psychologist, is known for his theory on “hierarchy of needs”. According to this, humans’ needs are classified in a pyramidal structure through a number of levels. At the bottom of the pyramid, there are most fundamental and physiological needs. Needs are ascending from this basic level to more complex needs like self-actualization at the top. As suggested by Maslow, it would be unreasonable to expect a desire for satisfaction of the needs at higher levels if one is already unable to satisfy the needs at a lower level. Each step towards the top of the stairs represent more complex and abstract category of needs.

Applying this framework to Middle Eastern water problems, we come across with the difficulty of integrating different categories of solutions across Three I’s. Because, such an integrative thinking needs a water management paradigm that had already achieved a certain level of “development” where discussing the needs like environmental sustainability or social acceptability is not a luxury.

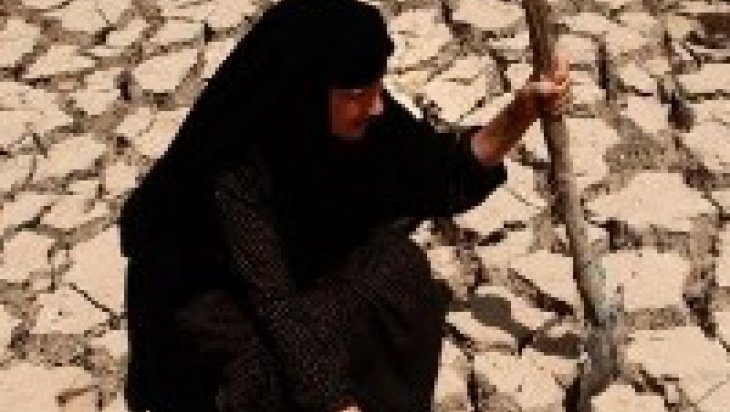

What is meant by this is that, most of the countries in the Middle East are still struggling with more direct or fundamental needs such as “access to water”, or achieving “water security”. It is the world’s most water-scarce region, and even developed and rich countries like Israel, or the United Arab Emirates are also trying hard to protect and if possible increase the availability of freshwater resources. Other countries like Syria, Iraq and Yemen are far worse in terms of the means to achieve water sufficiency. At current stage, protection of environment, for instance, is not an utmost priority for them. They are preoccupied with first supplying drinking water to their rapidly increasing populations. Thus, it would be premature today to offer solutions that goes beyond the perimeters of the actual water management needs and practices, and material capacities of the countries concerned. It is simply putting the cart before the horse.

However, this is not to say that let us ignore the environmental, or societal concerns. This would, too, be detrimental to what is needed by Middle Eastern countries. It is well-known that environmental sustainability is indispensible dimension of water management policy. But, priorities are quite pressing; and demanding more advanced practices from these countries would dilute the energy of the peoples of the region directed towards overcoming the difficult puzzle of water problem which has become even more challenging by rampant violence. Therefore, such proposals could, thus, be counterproductive at times, will be unrealistic and will likely be embraced only at the rhetorical level.

(1) Shahbaz Khan, Chief, Water and Sustainable Development Section of UNESCO, powerpoint presentation, on file with Author.