Cure for all the Water Woes in the Jordan Basin? An Analysis of the Red Sea-Dead Sea Project

Israel and Jordan agreedearlier this year on the multipurpose project of the “Red Sea–Dead Sea Canal”.The agreement which worth $800 millionwas the result of a Memorandum of Understanding signed among Israel, Jordan and Palestine on December 9, 2013, in Washington.

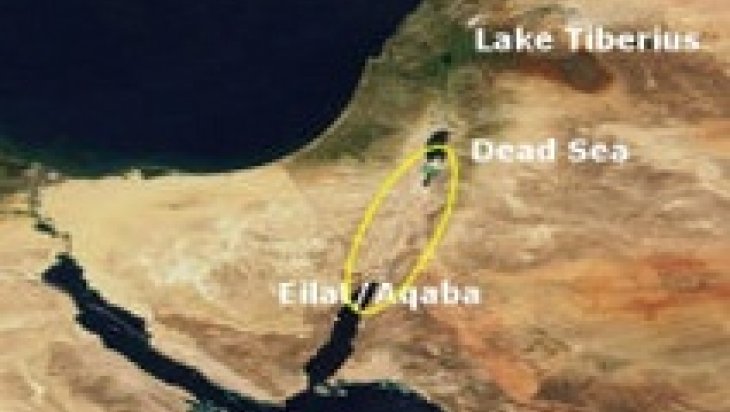

The project includes the construction of a 80millioncubicmeter capacity desalination plant in Aqaba, Jordan. According to media sources, Israel will buy some 35 million cubicmeters of water per annum from this plant. On the other hand, in accordance with the agreement, Jordan will buy an additional 50 million cubicmeters of water annually from Lake Kinneret, to use in its northern regions.As equally importantly, the agreement entails the construction of a 200-kilometer pipeline which wouldconvey brine water from Aqaba bay to the shrinking Dead Sea. The total cost of the project is estimated at $5 billion.

Main objectives of the project could be listed as follows:

a) To provide potable water to Jordan, Israel and the Palestinian territories.

b) To bring sea water to improve the Dead Sea water level.

c) To generate electricity to support the needs of the project.

d) To become a part of the comprehensive “Peace Valley Plan”

This proposal has a role in plans to create institutions for economic cooperation between Israelis, Jordanians and Palestinians, in the Dead Sea and through the Peace Valley plan.Although the agreement did not specify the case for Palestinian Authority, it was during the 2013 Memorandum of Understanding that Israelis were called for to provide (sell) additional water (some 20 million cubicmeters) to Palestinian Authority.

The agreement was signed on the Jordanian side of the Dead Sea by National Infrastructure, Energy, and Water Minister Silvan Shalom and his Jordanian counterpart, Water and Irrigation Minister Hazim el-Naser, in February 2015 in a ceremonial fashion. Two countries agreed to set up a joint administration for the project-related tasks. The joint administration will be based on equal representation of officials from two countries.

The expectations are high with the project. For instance, Saad Abu Hammour, the secretary-general of the Jordan Valley Authority within the Jordanian Water and Irrigation Ministry has told “This is the first regional peace project between the two countries after the peace treaty”. He stated that not only does the agreement have the potential to save the Dead Sea and solve the water shortage in two countries, it can build the peace process between the two countries. Abu Hammour was the min negotiator of Jordan during the talks between Israel. Israeli Minister has also told “today we are realizing the vision of Binyamin Ze’ev Herzl, the father of the state, who in the late 19th century saw the need to revive the Dead Sea,……..this is the most important and significant agreement since the peace treaty with Jordan. This is the peak of fruitful and very good cooperation between Israel and Jordan and will assist in rehabilitating the Dead Sea and in resolving water issues in Jordan and the Arava.”

Meanwhile, there are a number of criticisms about the project. Some of them are environmental criticisms. For instance, EcoPeace: Friends of the Middle East , a regional organization composed of Jordanian, Palestinian and Israeli environmentalists, opposed the idea of bringing brine water from Red Sea to Dead Sea on the ground that the Dead Sea has a unique water chemistry and the brine water from Red Sea may worsen the Dead Sea’s water status. EcoPeace also opposes the idea of carrying water from Lake Kinneret to Jordan through a pipeline. For the EcoPeace, the water from Lake Kinneret should directly be released to the River Jordan which gravely needs an increased flow. On the other hand, there is an opposition from Israel within. There are already four kibbutzim (kibbutz is the name of collective communities in Israel based on agriculture, plural: kibbutzim) send a petition to to the Israeli High Court of Justice arguing -like EcoPeace- that the water from Lake Kinneret should be released to the Jordan Rive so that Israelis could also benefit from this newly allocated water along the banks of the river. Finally, there are also Egyptian worries. Egypt have argued that the the canal will make seismic activity in the region rise. Egyptians also worried that the newly water from the Project may provide Israel with water for cooling its nuclear reactor near Dimona.

It is apparent that this has been one of the most important water projects in the Middle East with its wide ranging ramifications. If it succeeds with environmental harm at minimum, the Red Sea-Dead Sea Project may help to ease water stress in Jordan and Palestine, restore the Dead Sea, and serve a catalyst for further cooperation among all parties involved. However, beside the high cost of the project, the fragility of the relations among the concerned parties cast doubt on the fate of the ambitious Red Sea-Dead Sea Canal.