DAESH: A Neo-Wittfogelian Initiative?

“Oriental Despotism” is a great book. The author, Karl Wittfogel, a notable German-American expert on Chinese anthropology, writing in 1957, had argued that requirements of large scale hydraulic works were the main reason for appearance of despotic states in ancient times. According to Wittfogel, a powerful hydro-bureaucracy emerged in a setting characterized by Marxists as “Asiatic mode of production” which -primarily- was based on irrigation. In this, control of water supply, or in Wittfogel’s words, a “hydraulic monopoly” was the basis for ruling structure in such societies.

Thus, in a nutshell, since irrigation required substantial and centralized control, state authorities tended to monopolize political power and dominated the economy. The result was an absolutist managerial state, which is “above” the society.For Wittfogel these “hydraulic civilizations” included ancient Egypt, Mesopotamia, India, China, as well as pre-Columbian Mexico, and Peru.

Karl Wittfogel’s theorization created a great deal of academic debate. Wittfogel’s theorizing was generally criticized as being reductionist, i.e. seeing water control as the sole attribute for social organization. However, Wittfogel was careful enough to avoid such a deterministic fallacy from the outset by saying: “The opportunity, not the necessity. Large enterprises of water control will create no hydraulic order, if they are part of a wider nonhydraulic nexus. The water works of the Po Plain, of Venice, and of the Netherlands modified regional conditions; but neither Northern Italy nor Holland developed a hydraulic system of government and property. … Thus, too little or too much water does not necessarily lead to governmental water control; nor does governmental water control necessarily imply despotic methods of statecraft” (p. 12).Besides, Oriental Despotism was also –with good reason- criticized on the ground that Wittfogel’s theorization of hydraulic absolutism cannot be supported by archeological evidence. All in all, his general perception of water-absolutism link still continues to shed some light in the Middle East of our times.

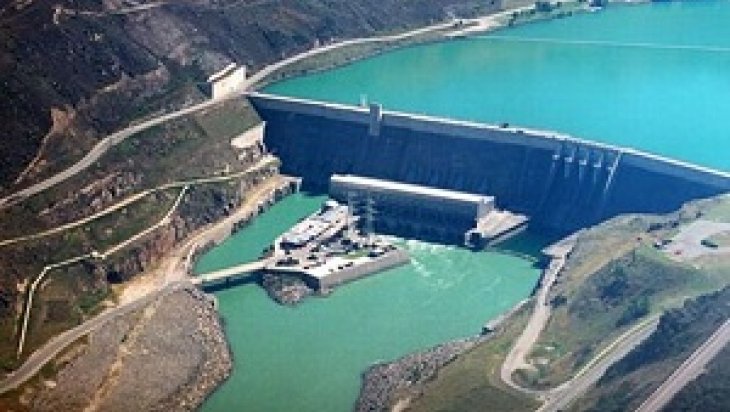

Half-a-decade rule of DAESH in Mesopotamia may provide a good milieu for discussing modern reflections of Wittfogel’s theses. Firstly, one needs to recap the significance of water resources for Mesopotamia. Water appears to be one of the backbones of political, economic, and social life in this part of the world. In relation to this central significance of water; dams, hydro-electric plants, reservoirs, irrigation canals serve highly critical and possibly irreplaceable purposes. Control of significant hydraulic structures in the region, thus, gives DEASH an immense power in economic dominance through energy provision, distribution of water for irrigation, and drinking purposes. It has used water related services as a means for consolidating loyalty of the masses. Beyond all, DAESH bluntly uses water as a weapon of war, at an unprecedented scale. All possible dangers of water are being utilized on a daily basis through constant threatening and occasionally practicing: flooding downstream, poisoning drinking water bodies, exploding dam structures, cutting off flow of electricity, and so on.

Such an exclusive control and use of this important resource resonates to what Wittfogel had analyzed some six decades ago. According to Wittfogelian terms, DAESH could conceivably be regarded as a “hydraulic state”: “The hydraulic state is a genuinely managerial state. This fact has far-reaching societal implications. As manager of hydraulic and other mammoth constructions, the hydraulic state prevents the nongovernmental forces of society from crystallizing into independent bodies strong enough to counterbalance and control the political machine” (p. 49).

It is wise though, to note that water is certainly not the sole axis which DAESH relied on for its totalitarian control. Oil, trade, and more importantly military power are other primary elements for it to sustain its rule over the territories and people under its control. But being a hydraulic state, i.e. unrivalled ability to control of water and related services through control of hydraulic structures has equipped DAESH with the definitive tool for sustained control of political landscape. Agriculture continues to be the basic economic sector in most of Mesopotamia where DAESH operates. Therefore, control and management of hydraulic works not only place the “large-scale feeding apparatus of agriculture in the hands of the state” but also makes the state as “the undisputed master of the most comprehensive sector of large-scale industry” which relies on agricultural production.

There is also another strong incentive for agriculture in DAESH-controlled areas. Since food prices in Turkey is noticeably higher than those in Iraq and Syria, illegal trade in food has become a lucrative business DAESH territories. So, with this “virtual water” trade opportunity, it is now less surprising to see an –otherwise counterintuitive- increase in net agricultural production figures in DAESH occupied areas. In short, along with strong internal motivations, there is an external yet influential pull factor for DAESH’s intense aspirations vis a vis water control.

To conclude, Karl Wittfogel’s Oriental Despotism is definitely not a conclusive account on development of absolutist states in water-centered societies in the past. It has several flaws as the relevant literature suggests. Social phenomena have always been more complicated and multifaceted than it may first seem. Regardless, Wittfogel has triggered a lively debate where more sophisticated and contemporary arguments on the salience of water in formation of organizational characters of states or state-like structures are thriving. In this framework, DAESH controlled areas provides an interesting case for further research.