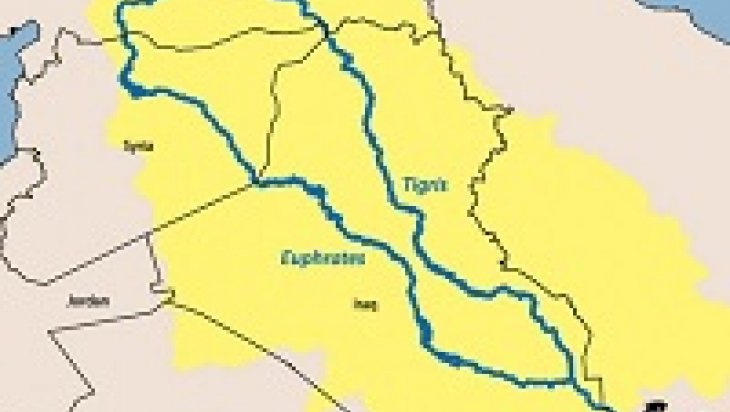

Water Politics along the Euphrates and Tigris: Why does not (and will not) Turkey Use Water as a Weapon against its Southern Neighbors?

Transboundary water relations among riparians of the Euphrates and Tigris are generally depicted as one of the so called “hot spots”, with an inherent propensity for war. Reaching its peak of popularity in 1990s. Water war scenarios basically focused around the grave water scarcity in the basin, which is exacerbated by increased irrigation and rapidly growing populations, concluding that Euphrates-Tigris transboundary basin will likely experience hot conflict at some point in time.

In a similar fashion, water hegemony literature tended to label Turkey as a water hegemon, in the context of Euphrates-Tigris transboundary basin. Given its superior geographical position in the headwaters of both Euphrates and Tigris, as well as its massive reservoir capacity, Turkey was argued to be quite powerful in dictating the “rules of the game”. Furthermore, it has been argued that Turkey is equipped with a power to turn off the tap if and when it desires. While this holds true at the theoretical level, it has never been materialized in the past, and there are numerous reasons that in the future, too, Turkey will not divert or cut off the flow of neither Euphrates, nor Tigris. It should also be noted that Turkey officially declared (in the context of Turkey-Syrian relations) that it will never use water as a weapon.

First and foremost, using water as a weapon will be regarded as a very very unfriendly move, not only by Turkey’s neighbors, but also by international community at large. Cutting off water will mainly hit the masses more than it will hurt the decision makers. Therefore, it is not a good leverage against the governing elite. It will certainly create pressures from society towards the government, but at the end of the day, Turkey will be the one to blame, not the government. If used as a weapon, water becomes indiscriminate in terms of the harms it causes, harming the poor most. Turkey is well aware of the fact that this kind of an action will also jeopardize Turkey’s prestige well as intentions in a wider international community in which it tries to utilize its soft power to maximize stability in its region ad beyond. Beside immediate reactions, this behavior will most likely continue to create resentments in both Iraq and Syria for -possibly- an indefinite period.

Secondly, water becomes a liability rather than an asset under the impacts of climate change. Let me explain. Recent internal conflict in Syria has demonstrated that displacement of people in a given country could well become a challenge for other countries in the region as well. Prolonged droughts in 2007 and 2008 played significant role as a threat multiplier in triggering out-flux of the agriculture (read “water”) dependent people from rural areas towards urban centers. In turn, these people have become the fire starter of the Syrian riots which then culminated into a full scale internal war. At the end, approximately two million Syrians have entered in Turkey resulting in a wide range of issues mainly decreasing the social stability in the recipient country. In such a background, perhaps counterintuitively, provision of water to people in Syria and Iraq is and will be in the interest of Turkey itself. In this sense, sustained water flow to these countries can have a pacifying and stabilizing effect. This, however, should not be overstated. Providing uninterrupted water for the Islamic State in Syria and Iraq, for instance, will not have such an effect. Overall, under normal conditions, and acting upon rational calculations, Turkey will not harm its neighbors by cutting off or decreasing enormously the water flow of the watercourses of the Fertile Crescent. In other words, in a cost-benefit analysis scenario, Turkey will continue to release equitable amounts of water from Euphrates and Tigris, as long as the costs of not doing so exceeds this cost.

Third, it is technically very difficult to divert or cut off waters of Euphrates and Tigris. While reservoir capacities in Turkey are substantial, they are not able to collect water for longer periods. Water is a fluidal substance which cannot be stored completely and forever. Therefore, unlike successful oil embargoes via suspension of oil production, water needs to be released. Because of this property of water, using it as a weapon could be counterproductive in not yielding results, apart from creating grievances.

In short, a closer look at the Euphrates-Tigris transboundary basin reveals the fact that contrary to alarmist accounts, despite its advantageous upstream position with a strong economic output and military structure backed by NATO, Turkey will maintain a reasonable and equitable water flow towards its downstream neighbors in the south. Water as a weapon remains to be implausible within the context of Euphrates-Tigris basin.